Tre’s pet parent, Charlene, tosses her thick auburn locks over her shoulder and chuckles awkwardly at her dog’s seemingly defiant behaviour. Her smattering of freckles fade behind a crimson bloom as she wrestles the bundle of energetic dog between her legs.

Tre’s pet parent, Charlene, tosses her thick auburn locks over her shoulder and chuckles awkwardly at her dog’s seemingly defiant behaviour. Her smattering of freckles fade behind a crimson bloom as she wrestles the bundle of energetic dog between her legs.

“Honestly, he’s so well behaved at home!”

Tre isn’t misbehaving, so much as wiggling. She attempts to smoosh back Tre’s lips to show me his teeth but he licks her fingers and then slathers her face. Tre is stunning. A two year old American Bully, with a sleek, black and brown coat stretched over bulging muscles. Technically he’s a fugitive in Ontario, persecuted under a breed ban—assuming that because of his breed alone, he’s destined for aggression. Which in my opinion is ridiculous. I’ve met more aggressive Shit-Tzu’s than Pitbull’s in my veterinary career.

Charlene, his owner and advocate, is overly sensitive to his every distress, as she’s been protecting him from people who would see him harm based only on appearances. She fends off glares and once, on public transit, a stranger approached and started lecturing her while pointing at her baby (Tre with his sad dog eyes) and declaring, “That dog should be destroyed!” –only because of his face.

His actions have never hinted at aggression towards humans, but his fierce red-headed pet parent might just go ballistic if someone tries to harm her precious Tre. I can’t help but respect her more for her passionate protection.

His actions have never hinted at aggression towards humans, but his fierce red-headed pet parent might just go ballistic if someone tries to harm her precious Tre. I can’t help but respect her more for her passionate protection.

She finally manages to force Tre’s smile by lifting his thick lips and flashing his teeth my way and I appreciate the reason for our visit today. Tre is hurting because of my lack of advocating for his needs. As his veterinarian, I’ve managed to let both him and his owner down.

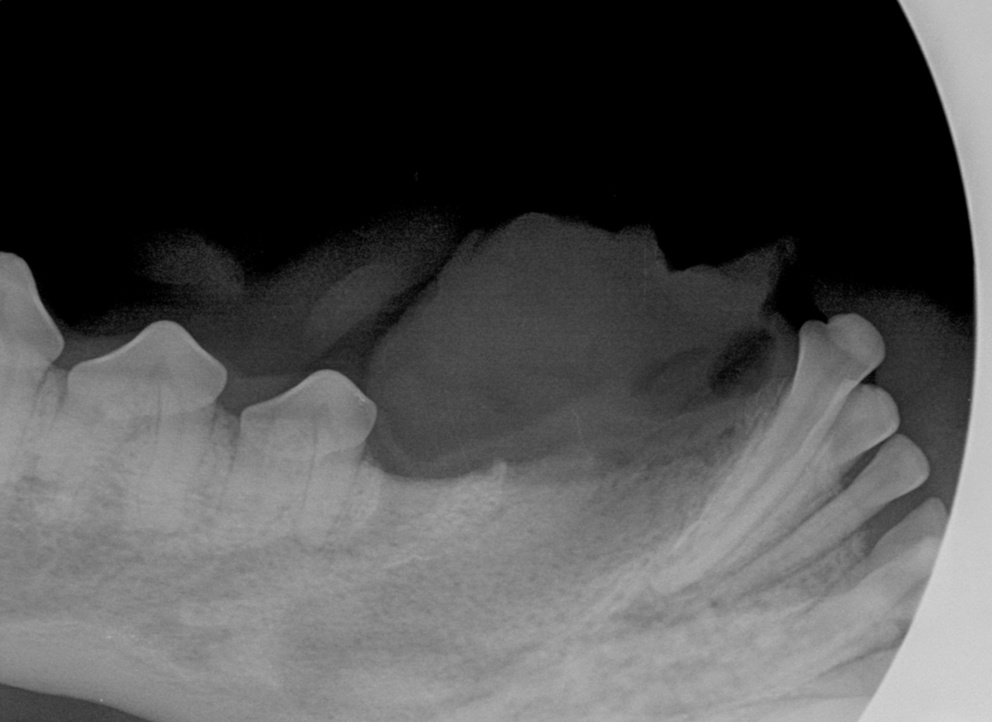

When I first met Tre, Charlene brought him in for me to examine his teeth. Fate (and maybe an unscrupulous breeder) dealt Tre a poor hand when it came to the genetic shuffle. He has a malocclusion where his lower jaw is too short. So, instead of his lower incisors snugging up comfortably behind his upper incisors, they are a good inch behind. This would normally be disastrous, if not for the fact he has somehow fractured off his lower canines. If his canines were full height they would impale into the soft flesh behind his upper canines, possibly eventually puncturing into his nasal cavity.

When I first met Tre, Charlene brought him in for me to examine his teeth. Fate (and maybe an unscrupulous breeder) dealt Tre a poor hand when it came to the genetic shuffle. He has a malocclusion where his lower jaw is too short. So, instead of his lower incisors snugging up comfortably behind his upper incisors, they are a good inch behind. This would normally be disastrous, if not for the fact he has somehow fractured off his lower canines. If his canines were full height they would impale into the soft flesh behind his upper canines, possibly eventually puncturing into his nasal cavity.

As a developing veterinarian, I learned a great deal from my mentors. One piece of advice I heard time and time again was in regards to these fractured and discoloured teeth in adult dogs.

As a developing veterinarian, I learned a great deal from my mentors. One piece of advice I heard time and time again was in regards to these fractured and discoloured teeth in adult dogs.

Only a few short weeks ago, I passed this advice onto Tre’s owner.

Previously, when Tre’s owner saw me wince as I took in the dark pitting holes on the surfaces of his fractured lower canines, she said, “They’ve been like that since he came to us. He had separation anxiety as a puppy and tried to eat his way out of everything.”

I turned from side to side, noting four fractured canines with their muddy, less vibrant colouring in contrast to his other vital white teeth. It’s possible Tre had separation anxiety and chewed on his crate, but I also wonder if the pain and distress of not being able to close his mouth comfortably was confusing and distressing enough to sadly, make him break off his own teeth.

So, I passed on what I’d heard other vets say, time and time again, “It shouldn’t bug him. Let’s keep an eye on them.”

Now, Tre is here today to teach me how that advice was not the whole story.

I lift Tre’s lip and run my thumb over his lower right canine, the ivory of his tooth tan instead of pearly white, with a dark pit, like a cavity, on the flat surface. Behind this tooth, on the gum, there’s a raw, bright pink, fleshy hole and his lower lip is so swollen it’s as if he’s pocketing a plum for later. His eyes, normally bouncing across my face, searching for the next opportunity to please, are triangular and squinted in pain.

I lift Tre’s lip and run my thumb over his lower right canine, the ivory of his tooth tan instead of pearly white, with a dark pit, like a cavity, on the flat surface. Behind this tooth, on the gum, there’s a raw, bright pink, fleshy hole and his lower lip is so swollen it’s as if he’s pocketing a plum for later. His eyes, normally bouncing across my face, searching for the next opportunity to please, are triangular and squinted in pain.

This is the limit to which Tre will complain. He will not lay on his bed and toss his paw over his head in agony. He will not search out a cold compress from the fridge to lay across his swollen jaw. He won’t wrestle into the Tylenol bottle to pop pain relievers and most of all, even though he has a fever and is in pain—he will not stop eating.

Pets don’t complain like we do.

He may not play with his toys the same. He may chew his food on the other side of his mouth. He may be a little quieter or in truth, he may not show any signs of discomfort at all. This is normal.

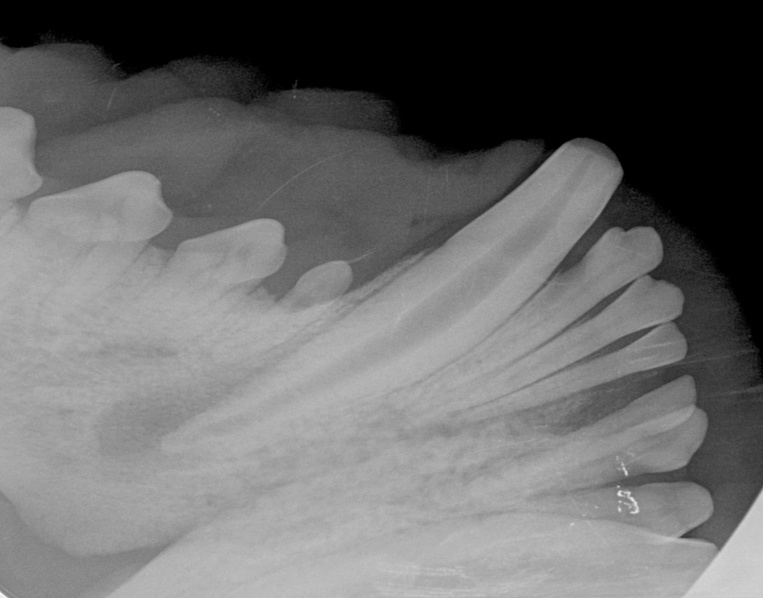

However, from the radiograph that demonstrates the destruction of his root tip and the swathed path of bone loss the infection has burrowed through his mandible to erupt out that draining hole in his gum tissue, I can hardly imagine the pain and discomfort this tooth has caused Tre.

However, from the radiograph that demonstrates the destruction of his root tip and the swathed path of bone loss the infection has burrowed through his mandible to erupt out that draining hole in his gum tissue, I can hardly imagine the pain and discomfort this tooth has caused Tre.

When I place a dental probe into the hole on the surface of his fractured tooth, a well of tan, foul smelling puss spurts up and runs down over his tooth. Charlene’s eyes widen and she places the back of her hand over her slack mouth.

By not advocating for Tre, I’ve allowed this condition to get much worse.

Fractured teeth hurt. They hurt when they are broken, and then they hurt and ache afterward. If the pulp canal is open to the world, this can act like a straw for infection. Pulling bacteria into the root and then into the jaw bone.

I know now, that had I advocated for Tre, and advised Charlene earlier that these fractured teeth were at risk for infection, tooth root abscesses, bone loss and draining tracts, I may have prevented Tre’s discomfort and the suffering he must have been enduring these last weeks.

I know now, that had I advocated for Tre, and advised Charlene earlier that these fractured teeth were at risk for infection, tooth root abscesses, bone loss and draining tracts, I may have prevented Tre’s discomfort and the suffering he must have been enduring these last weeks.

Advised correctly, Charlene could have taken action to prevent this suffering. For years I saw these damaged teeth and failed to educate owners of all the possible outcomes.

A couple weeks later, I literally drag our fourth year veterinary externship student into the exam room and introduce Charlene and Tre. Tre squiggles up to us, his body snaking from side to side. In his excitement he can’t decide if he wants to sniff us, or present his bum for scratches, so he dances sideways and then finally flops his whole body against my leg.

Charlene pulls on his leash ineffectually and calls out, “Tre, Tre!” laughing all the while.

Charlene pulls on his leash ineffectually and calls out, “Tre, Tre!” laughing all the while.

Thoroughly licked clean of the guilt I still hold for Tre’s suffering, I introduce Tre to my student and share his entire story. Then I pause as I hold back Tre’s lips to show the healthy pink scar from the surgery where we removed his lower canine.

I release Tre’s lips and make eye contact with this future veterinarian, “We need to look in our patient’s mouths. We shouldn’t ignore these fractured and discoloured teeth. It’s up to us to help owners see and understand.”

Tre slides down my leg to expose his most vulnerable self, asking only for a belly rub, which I happily give.